By Michael Zhang, Head Designer

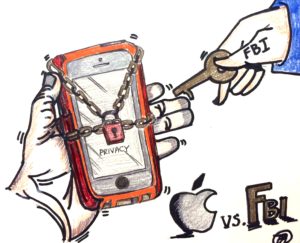

Cartoon by Pallavi Aakarapu

Chances are that in the last two weeks, you’ve seen at least some news about the latest dispute between government and technology. The FBI wants Apple to help unlock an iPhone used by one of the attackers in the San Bernardino shooting last December, and despite going up against a federal agency and a federal court order, Apple won’t do it. Now, in a classic case debating the ideal medium between privacy and security, the technology company’s defiance might seem unreasonable. There could be crucial information regarding the terrorist attacks on the phone, and it makes sense that in order for the public to enjoy more security, it must be willing to sacrifice some of its privacy. But such a case only applies to the picture that the FBI is trying to paint, one that’s shaping a Pew Research Center majority poll opinion that Apple should unlock the late terrorist Syed Rizwan Farook’s iPhone 5c This picture fails to capture the entire story. And understanding how it doesn’t is crucial to seeing why Apple is right in challenging the court order to comply.

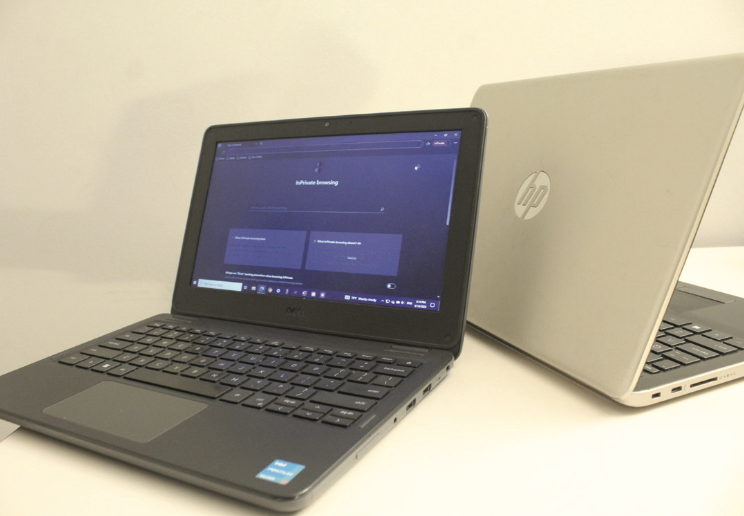

On Feb. 16, Federal Magistrate Sheri Pym issued a court order requiring Apple to help the FBI hack into Farook’s phone, bypassing its encrypted security system to see what’s inside. Legally, the phone is in the government’s possession, and not taking into account anything else, no one has any issue with infringing upon the privacy of a dead terrorist responsible for the loss of 14 innocent lives. But considering how Apple would actually go about unlocking the device is when things start to get complicated. In order to get past the iPhone’s security, what the court and the FBI are telling Apple to do is create custom software that would let the FBI run a brute-force password-cracking algorithm on the device. Unfortunately, while the FBI is only after Farook’s phone, the piece of hacked software it wants Apple to make isn’t. As stated by Apple CEO Tim Cook, “in the wrong hands, this software—which does not exist today—would have the potential to unlock any iPhone in someone’s physical possession.”

And there are issues with the court’s order in the right hands too. The software the FBI wants would create a vulnerability exploitable in any iPhone, and Apple’s compliance to create a backdoor does more than undermine its engineer’s efforts to devise protective mobile security systems. By defying the order, Apple is taking a step in preventing undue access to its consumers’ privacy. Once the software goes out, even if it’s only directed to the government for the purpose of unlocking Farook’s phone, it’s very possible that it will be usable beyond the FBI and on the terrorist’s device. The FBI has admitted that it’s possible that they won’t find anything on the phone in question, but a device without any more terrorism links won’t stop medical records, financial data and everyone else’s innocent information from being stolen.

What’s also at stake is a legal precedent, one in which if Apple complies, could allow the government to force any technology company to create new software for any variety of needs. There were other ways to get into Farook’s phone to collect evidence in a technology-connected society and do their job in maintaining public safety. Online data is searchable by warrant. Edward Snowden already unveiled the massive public surveillance capabilities and activities of the NSA. And it’s not impossible that the hacked software the FBI wants Apple to create has already been secretly written by the government. But to forgo all these possibilities and demand that Apple comply through court is to set the stage for a dangerous precedent undermining the protection of our privacy.

Yes, the FBI is trying to keep us safe from harm. But what the federal agency isn’t factoring in is that the methods described in its dispute with Apple make all of us less secure. It’s sometimes hard to believe how much technology has become a digital extension of ourselves, but it’s important to consider the implications a pro-FBI precedent could have in undermining the already fragile notion of personal privacy. FBI v. Apple is not just a privacy debate regarding one terrorist’s outdated iPhone. The stakes are huge here, in obtaining the necessary justice and preserving public safety, but also in assuring the security of the worlds we live in today and tomorrow.

Michael Zhang can be reached at [email protected].