When watching women’s hockey, from local high school rinks to the Olympics, viewers may notice a key difference from the men’s game: the lack of body checking. Body checking is intentional contact to separate an opponent from the puck as defined by USA Hockey, and it is banned for all girls, women, and 12U and under leagues.

According to a 2014 NCAA study, collegiate women’s ice hockey has the highest rate of self-reported concussions out of any sport, regardless of gender. Some of this can be explained by factors like neck strength or hormone levels, but another reason may be that female hockey players are not trained to expect or absorb contact the way that their male counterparts are. This often leads to dangerous habits, such as skating with their heads down.

Since the distinction between incidental contact and illegal checking can be blurry in a fast-paced play, the referees cannot consistently enforce rules, leading to the opening minutes of many games becoming a test of how strictly referees will call physical play. Legalizing checking can remove that uncertainty and allow players to focus on strategy and skill, rather than guessing the mood of the referee.

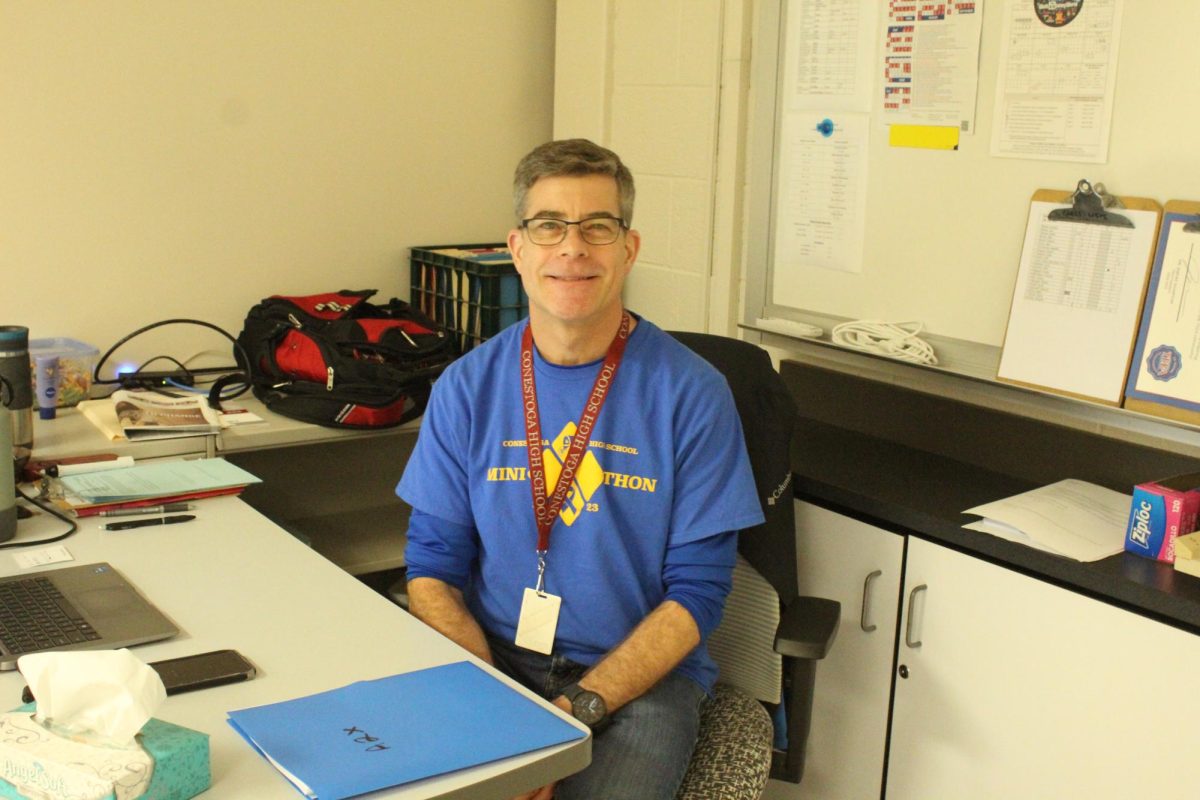

“As long as (physical play) is taught correctly as it’s being done these days, even in boys hockey, if you’re not out to physically injure somebody, (and) it’s truly to get the puck away from another player, (then) physical play, in my opinion, is not a bad thing,” Conestoga girls ice hockey head coach Christopher Hellmann said. “I would be in favor of it again as long as they take every precaution to teach it the right way.”

The North American-based Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL) has allowed checking since its inception in 2024. In an AP article, Minnesota Frost coach Ken Klee, a former NHL player, said it was important for players to take “ownership of protecting themselves. It’s not just the ref’s job to protect them.”

Other full contact sports, such as rugby and football, maintain the same rules for women and men. While early hockey games in the 1940s allowed rough play, checking was nearly fully banned worldwide soon after, with officials citing that women were “too delicate.” The lingering need to “protect” women from the nature of hockey has sexist undertones and hinders the legitimacy of women’s hockey as “real hockey.”

As a player, I can appreciate the skilled stick handling, frequent passes and tactical play that often define women’s games. Allowing checking won’t erase those strengths, nor will it encourage violence and fighting as seen in the NHL. Even in the PWHL, severe penalties are in place for illegal body checks, such as open-ice hits or checking a player who has their back turned.

While injury rates may increase slightly at first during the adjustment period, female athletes will eventually learn to hit safely and purposefully and can use it as a tool to create more space offensively and play with greater awareness. Revising the rulebook for women’s ice hockey to allow body checking will level the ice by encouraging better playing habits and dismantling the sexist belief that women cannot handle physicality.

Miya Cao can be reached at [email protected].