At the Oscars on March 2, Palestinian director Hamdan Ballal won Best Documentary Feature Film for “No Other Land,” a film that tells the story of Palestinians’ fight to protect Masafer Yatta, a collection of villages in the Hebron Hills of the West Bank.

But violence — and a murder attempt — challenged that victory. On March 24, a group of Israeli settlers beat and kidnapped Ballal in his village of Susya, where the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) later detained him. After the IDF released him, he reported in a March 27 interview with the news organization Middle East Eye that, from hearing the settlers shouting his name and “Oscars,” he concluded that the attack was in response to his Academy Award for the politically-charged film.

This day and age is no stranger to the censorship of people who challenge injustice. Haing S. Ngor, a Khmer actor who won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in 1985, played the role of a journalist named Dith Pran in “The Killing Fields,” a biographical film titled after the mass execution sites amidst five years of genocide under the Khmer Rouge regime that buried more than 1.3 million bodies in Kampuchea Province, Cambodia. A survivor of the regime, Ngor participated in the filming process seeking to expose Pol Pot, the leader of the communist regime, and his brutal intentions of erasing threats to his power and creating a “rural peasant population” under his rule. However, eleven years later, even after Pol Pot was overthrown, three gang members of the Khmer Rouge assassinated Ngor outside his San Francisco home because of his involvement in the film.

Both Ballal and Ngor spoke out against their governments and set examples to shed light on the cruelty inflicted on their people. Yet in return, they received severe backlash, and their resistance ultimatley led to deadly consequences.

Readers may remember my op-ed last April titled “Why I won’t celebrate the Cambodian New Year the way I used to,” where I delved into my parents’ own traumatic stories of escaping the genocide and the concerning trend of disparities that many Cambodians experience, one of them being censorship. As much as I find myself passionate about journalism and bringing their stories to light, my parents still hesitate encouraging me to do so — and for valid reasons.

Reporting the news — and especially writing opinions on sensitive topics — poses risks compared to pursuing a safer field like computer science in the comfort of my home. I recognize that my parents’ main goal in life was to raise a family, and being one of their only two children, I know that the thought of losing me is one of their biggest fears.

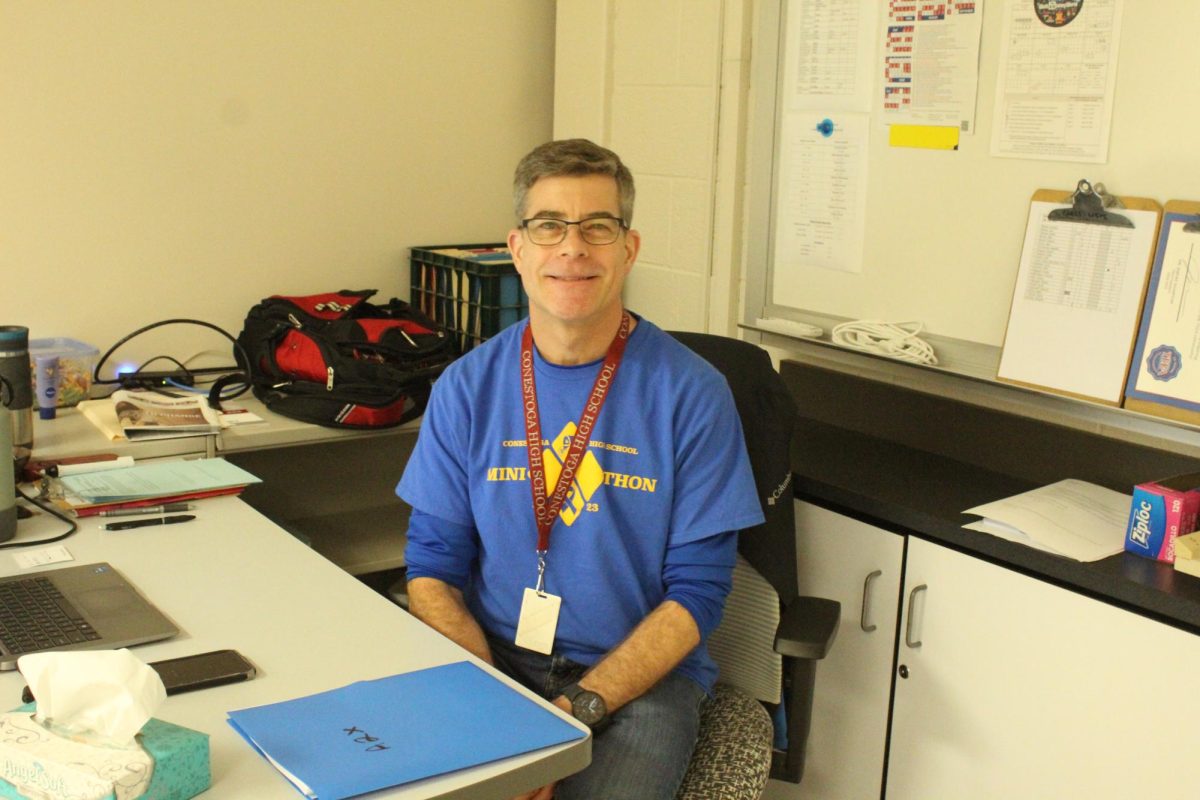

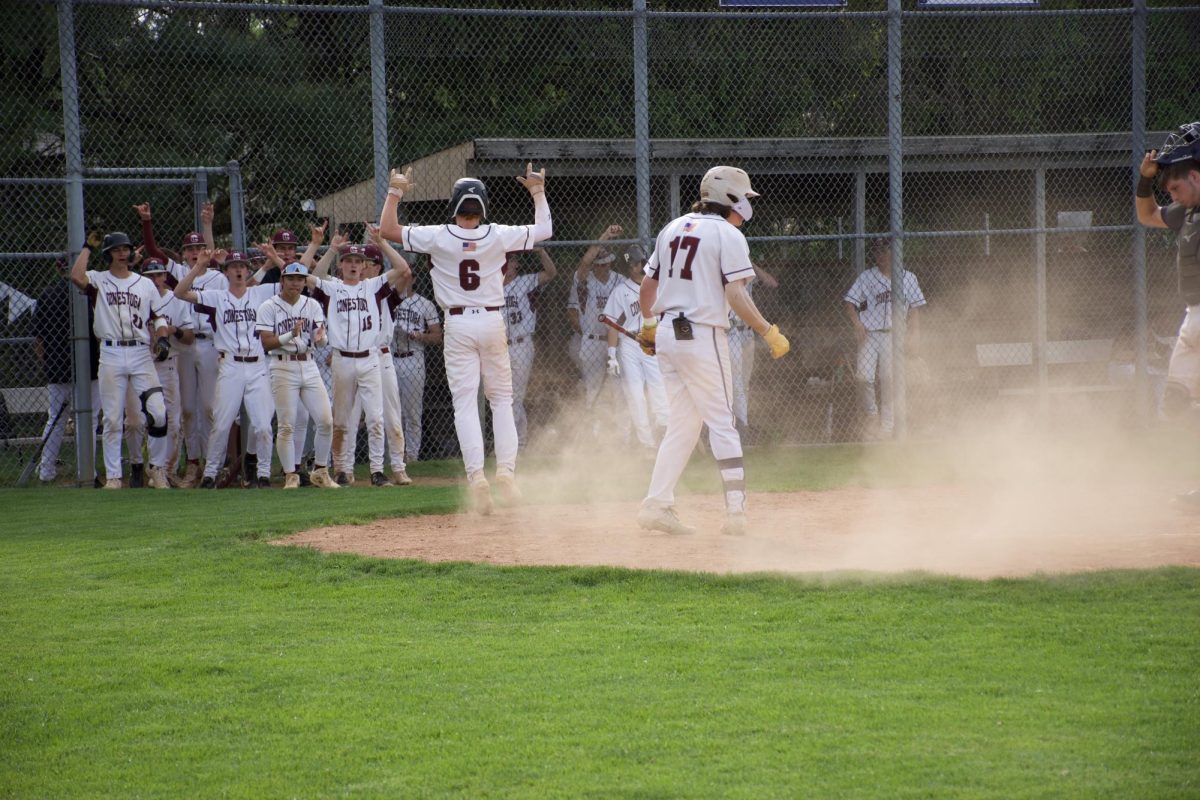

However, it is what Ngor and Ballal have done that inspires me to break boundaries in journalism because the experience for a 17-year old at Conestoga High School is completely different. Our resources and connections to the global sphere have never been more accessible with the technology we have now.

These two Oscar-winning activists are the reason I pay homage to those who remain fearless in telling untold stories, because the more people who are scared to speak louder about significant issues, the more prone we are to censorship — especially when it feels as though telling the truth is like asking for a death sentence.

Journalism gave me the platform to tell the story of my parents, injustice, turmoil and heartbreak. Regardless of what your relationship is with storytelling, our voices are the most important factor in ensuring our grievances don’t become our only takeaways from history. Never let your voice be silenced.

Jeffrey Heng can be reached at [email protected].