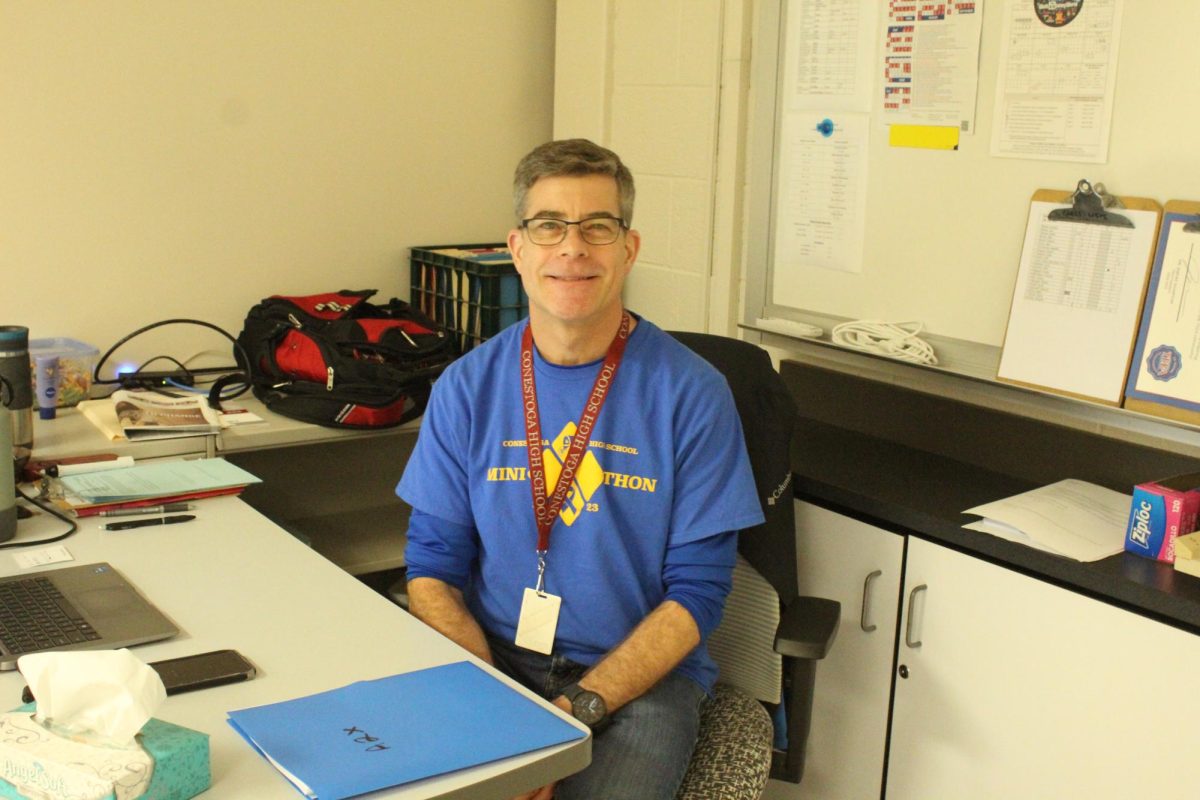

By Jeffrey Heng, Co-Opinion Editor

In fifth grade, I got into a physical fight with my classmate.

I was the one who had inadvertently initiated the fight, not knowing the consequences of my actions. Both of us faced punishment, but while I had an assigned lunch detention, which I never attended due to the administration forgetting about it, he was suspended for the rest of the week. I was the one at fault, yet it was my peer who ultimately got the short end of the stick.

Many schools in the United States use disciplinary actions such as suspension, expulsion and detention to foster a positive school climate in their buildings, including Conestoga. According to the Pennsylvania Department of Education, there were 157 recorded instances of violations of the Code of Conduct in the 2018-19 school year in TESD. After School Detentions, Evening Supervised Studies and Saturday Detentions are just some of the disciplinary methods listed in ’Stoga’s Code of Conduct.

However, these practices fall under exclusionary types of discipline that ostracize students from the educational setting and ultimately degrade their growth in the long run. Rather than emphasizing these strategies, schools should stress the importance of restorative justice.

Restorative justice is the practice of holding people responsible for their actions by repairing harm and mending relationships. Instead of suggesting the harsher connotation of discipline, it focuses on reparation between the individuals who may be affected by conflict.

For the 2020-21 school year, ’Stoga’s administrative team revised the Code of Conduct to include Restorative Practices (RP) in Policy 5401 as a “consequence for inappropriate behavior.” It states that students under this policy would “participate in an accountable, restorative intervention that addresses specfiic issues and behaviors” through the use of peer mediation, verbal correction, and written reflection or apology.

The number of infractions dropped from 157 instances in the 2018-19 school year, when there was no mention of RP in the handbook, to just 22 instances in the 2022-23 school year, possibly showing that the implementation of RP had notable impact.

Despite this change, no handbook in TESD middle and elementary schools makes any references to RP.

While traditional discipline may be necessary in certain cases, it often falls short of resolving conflict and instead builds anxiety in individuals. We are taught that the solution to our wrongdoings is isolated self reflection when our focus should really be teaching people to take that first step: being honest with themselves. Rather than investing time into practices that alienate students, schools and parents must truly consider the process of reconciliation and educating youth early on in elementary and middle school on restorative justice, to recognize those who are harmed and allow room for redemption.

Conflict can’t — and shouldn’t — be resolved by removing those impacted by conflict from classrooms and the community and putting them in detention or suspension. Reparations are most effective when disparities are addressed and mended directly between individuals.

Six years ago, I was an 11-year-old boy who didn’t know how to take accountability for my actions. And it’s six years now that I wish I had properly apologized to my wrongly punished classmate.

To my fifth grade classmate — if you’re reading this, I invite you to reach out, so I can repay you with the proper apology you deserved years ago.

Jeffrey Heng can be reached at [email protected].