By Miya Cao, Co-Copy Editor

If you bring up finance anywhere, chances are you’ll hear people mention the movie “The Wolf of Wall Street.” The tale of the narcissistic financial fraudster Jordan Belfort and his wrongdoings has changed the way young people see Wall Street. The image of serious men in suits remains, but there is a certain dramatic appeal that was not present before the movie came out in 2013.

Although the industry is broad, most people refer to entry-level analysts who do the grunt work of providing financial services to corporations as investment bankers. The obvious perk is the salary, ranging from $70,000-$90,000, with performance bonuses that could double the total compensation received. The rigor and prestige of the job also lead to invaluable exit opportunities in higher finance or other industries.

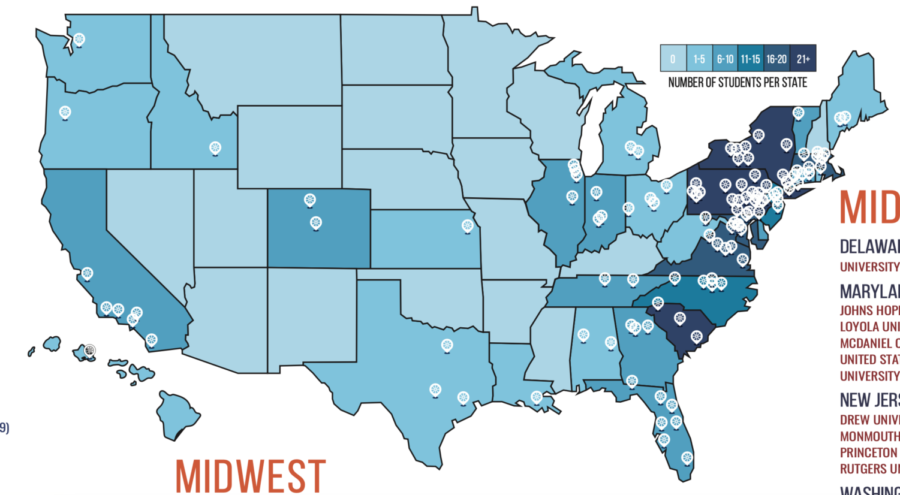

In recent years, banks have upped their recruitment efforts at elite colleges. They play into the competitive nature of high-achieving students, with internships starting the summer after freshman year. This pre-professional culture can become toxic quickly and also can begin in high school. College admissions culture is notorious for placing too much emphasis on prestige and rankings, but it forces students into a vicious cycle of chasing the next milestone.

In author Kevin Roose’s book “Young Money” about entry-level analysts, he describes how he “saw disillusionment, depression, and feelings of worthlessness that were deeper and more foundational than simple work frustrations.” Entry-level analysts are not respected on the corporate ladder and can face verbal abuse for simple mistakes. Most of their 100-hour workweek is not spent doing work, but waiting for it. As one analyst explains in “Young Money,” the worst part is the lack of control of your working hours and feeling like your life doesn’t belong to you anymore.

The banks convince students from all majors and backgrounds that they can empower students to achieve their dreams of anything from societal validation to venture capitalism, but only if they give the banks their lives for two years. However, these two years can morph into an extension of college and delay serious life and career decisions. People join the industry for a variety of reasons, but one commonality is that many expect to leave after two years. They get used to a lifestyle that almost no other industry can fund, especially when their earning potential skyrockets the longer they stay. They don’t want to move “backwards” in their careers to a less prestigious position, even at the cost of their health and relationships. Students are primed for salarial success, with an Ivy name on the wall and pressure to pay off student debt, but their careerism lacks true purpose and direction.

It’s okay to not know what you want to do, to pay off your student loans, to challenge yourself and to explore genuine interests. But, you should know that working a certain job will only delay, not solve your problems. Cancel that coffee chat; instead, have a chat with yourself: Who are you doing this for?

Miya Cao can be reached at [email protected].