By Tanisha Agrawal, Co-Sports Editor

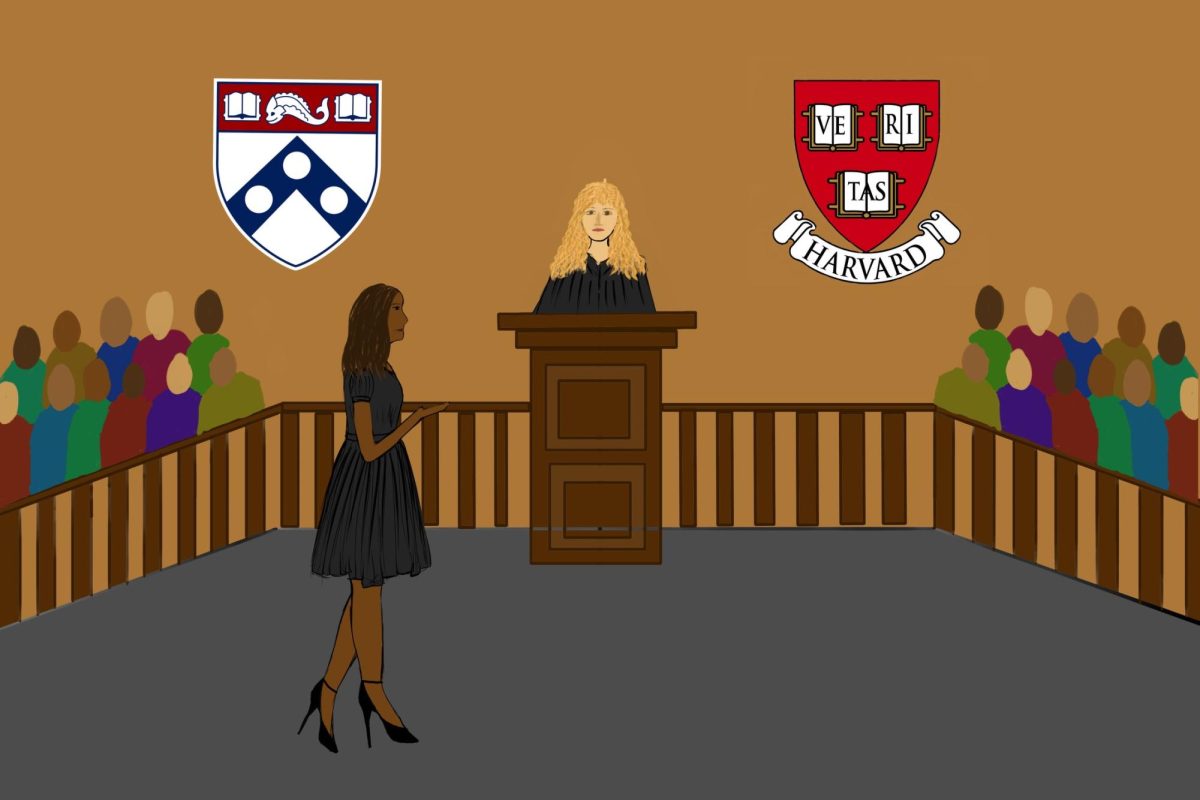

Since Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, hundreds of student demonstrations have swept the nation, including clashes between pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli students. Amidst the charged atmosphere, a significant development shook the foundations of the Ivy League: the resignations of Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania’s presidents, Dr. Claudine Gay and Liz Magill.

On Dec. 5, the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce called the presidents of Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Pennsylvania for a five-hour hearing. The Republican-led committee chose the three leaders because their schools “have been at the center of the rise in antisemitic protests,” a committee spokesperson said in a statement.

New York Republican Rep. Elise Stefanik asked the three presidents if “calling for the genocide of Jews” goes against the universities’ codes of conduct. All three said the answer depended on the context and circumstances. Magill responded that “if the speech turns into conduct it can be harassment” and that whether a student would be punished is “a context-dependent decision.” Gay responded, “It can be, depending on the context.”

The White House, donors, students and alumni met these statements with backlash. Donors threatened to pull major funding from the universities, influential alumni issued public calls for resignations for Magill and Gay. On Dec. 9, Magill stepped down, and on Jan. 2, Gay resigned as well.

At the same time, Gay faced plagiarism allegations in her published scholarly works. While she has not explicitly listed a reason for her resignation, it is likely due to the criticism over her comments in the Congressional hearing and accusations of plagiarism.

The testimonies and resignations may seem resolute, but unfortunately, they have only deflected the real issues: the role of universities in moderating free expression and the safety of students. Since the beginning of the Israel-Hamas war, students and professors have criticized the university presidents for showing a lack of sympathy for the Arab and Jewish student body. After the presidents’ statements during the hearing, Jewish and Arab students have shared feeling increasingly unsafe and neglected by the universities’ leadership.

As new leaders begin their terms at Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania, it is important to investigate what Gay and Magill could have done differently. The lessons learned will equip future university leaders to prevent similar tensions in upcoming conflicts.

This is what university leadership should be doing:

- University leaders are not political figures. It is their responsibility to protect students and see the best vision for the university and should not be held accountable to political agendas. In hindsight, Gay and Magill should have not testified in the hearing simply to avoid a high-risk situation in which hidden political agendas existed. Congress also asked Columbia University’s president Minouche Shafik to appear before the committee to testify about antisemitism on Columbia’s campus, but Shafik cited a “scheduling” conflict and did not attend.

- University leaders should refrain from succumbing to donors’ unrealistic demands to issue statements. While donations are imperative to run a university, donors’ rights should be limited and must not be allowed to interfere with university operations. Their external influence can significantly damage the independence of a university and set a wrong precedence for future donors.

- University leaders are responsible for addressing hate speech with appropriate consequences. Universities are institutions for learning which can happen only through respectful debates and discussions. Hate speech leads to increased fear and polarization as well as a lack of psychologically safe spaces for debate and discussion, which are against the principles of a university. While it can be difficult to discern what is and is not hate speech, advocating for direct calls of the genocide of any group or individual should be dealt with decisively.

- University leaders should organize events during tense periods to foster unity among students instead of testifying in Congress. In October 2023, Harvard’s Religion and Public Life Divinity School hosted a Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Solidarity for Just Peace in Times of Conflict event. The event facilitated a dialogue among scholars from diverse religious backgrounds, facilitating deep discussions on faith-based activism and international solidarity. Such events contribute to open dialogue and can alleviate tensions between student groups.

In recent months, free speech issues on campuses have become prominent. However, these problems extend beyond the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In times of conflict, college administrations should prioritize student safety over political agendas, donor influences and media trials.

Amidst the rubble of conflict, universities hold the power to build bridges of understanding, proving that unity and respect overpower even the most fertile grounds of dissent.

Tanisha Agrawal can be reached at [email protected].