By Ben Shapiro and Remington Vaughan, News Editor and Staff Reporter

Pennsylvania Commonwealth Court Judge Renee Cohn Jubelirer ruled that Pennsylvania has failed to equitably fund public schools. On Feb. 7, 2023, Jubelirer wrote in her ruling that “Students who reside in school districts with low property values and incomes are deprived of the same opportunities and resources as students who reside in school districts with high property values and incomes.”

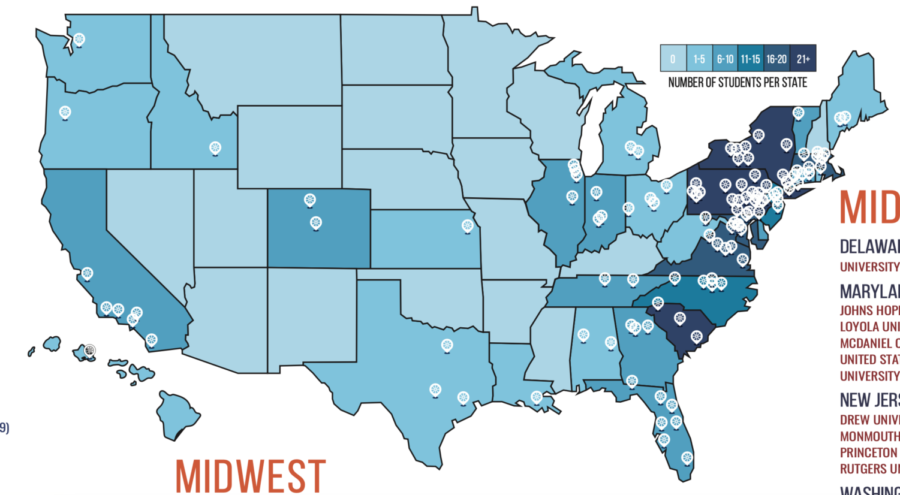

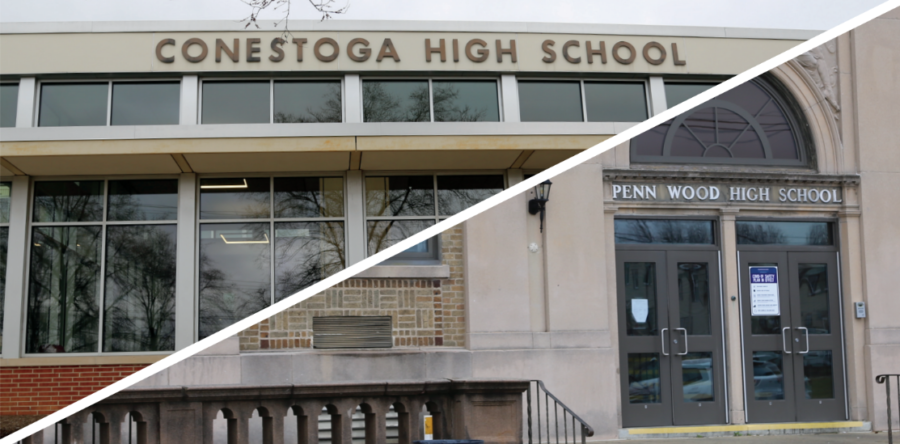

Six school districts — Greater Johnstown Area, Lancaster, Panther Valley, Wilkes-Barre Area, William Penn and Shenandoah Valley — along with the Pennsylvania Association of Rural and Small Schools, the NAACP of Pennsylvania and individual families came together as plaintiffs to fight the disparities within the current funding system.

“The plaintiffs (were) interested in seeing a funding system that more equitably provides for educational resources for students,” said Kati Robson of O’Melveny & Myers LLP, the counsel representing the plaintiffs.

The plaintiffs originally brought the case to the Commonwealth Court in 2014 in William Penn School District, et al. v. Pennsylvania Department of Education, et al. However, the judge ruled that the case was non-justiciable, or incapable of being decided by legal principles or a court.

“Respondents originally filed preliminary objections to the Petition for Review, alleging, among other things, that this matter involved political questions and, thus, was not justiciable under separation of powers principles,” Judge Jubelirer wrote in her ruling.

The respondents included the Pennsylvania Department of Education, the Pennsylvania State Board of Education, the Pennsylvania Senate and House of Representatives, and then-Governor Tom Wolf.

The plaintiffs appealed the 2015 ruling to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court which ruled that the case was, in fact, justiciable and sent it back down to the Commonwealth Court.

Once the court allowed the plaintiffs to make their case, the plaintiffs brought forward their main claim: that the Fair Funding Formula — the method by which Pennsylvania determines the funds it gives to each public school district — negatively affects school districts across the state.

According to the House Appropriations Committee, the Basic Education Funding Commission’s Fair Funding Formula is student-based, meaning a district’s share of state funding is tied to its share of the student population. However, each school district is not given the same funding per student.

“It (the Fair Funding Formula) is not a perfect formula. There’s a lot of districts that do not fare well from that, and there’s other districts that fare extremely well from it. It’s probably an unnecessary evil, if you will, where at least something’s in place to fund schools,” said Dr. Edward Albert, the Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Association of Rural and Small Schools.

According to Robson, the process to create a more equitable system of funding started with two steps. The first was to prosecute the proposition that children in Pennsylvania had the right to a certain standard of education — the definition of which is currently in contention. Then, the plaintiffs had to prove that the state was not meeting its constitutionally-required standard of education in some school districts as a direct result of the funding mechanisms.

“We are very gratified by the court’s decision that students in Pennsylvania have a fundamental right to a thorough and efficient system of education,” Robson said.

The future of public school funding policies

Although Jubelirer ruled that Pennsylvania’s funding allocation process for public schools is unconstitutional, she did not specify how the state should resolve the issue. Instead, she placed the responsibility of creating a new system in the hands of Gov. Shapiro, school districts and lawmakers.

Additionally, she gave no timeline for when they must have a resolution. In her ruling, she specifically stated that the plan need not be entirely financial.

“The options for reform are virtually limitless. The only requirement, (imposed) by the Constitution, is that every student receives a meaningful opportunity to succeed academically, socially, and civically, which requires that all students have access to a comprehensive, effective, and contemporary system of public education,” Jubelirer wrote in her ruling.

In May 2022, Gov. Shapiro filed an amicus curiae brief in support of the plaintiffs. An amicus curiae, or “friend of the court,” is a brief supplied to a court of law containing advice or information relating to a case from a person or organization that is not a party to the case.

“This Court should rule in favor of Petitioners and conclude that the General Assembly is violating its obligations under the Education Clause to provide all Pennsylvania children with a comprehensive, effective, and contemporary public school education,” Shapiro wrote in his amicus curiae.

Although the defense can still appeal this case to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and the Commonwealth Court ruling is not the final word, some school districts are hopeful about what the decision may mean for their schools and student populations.

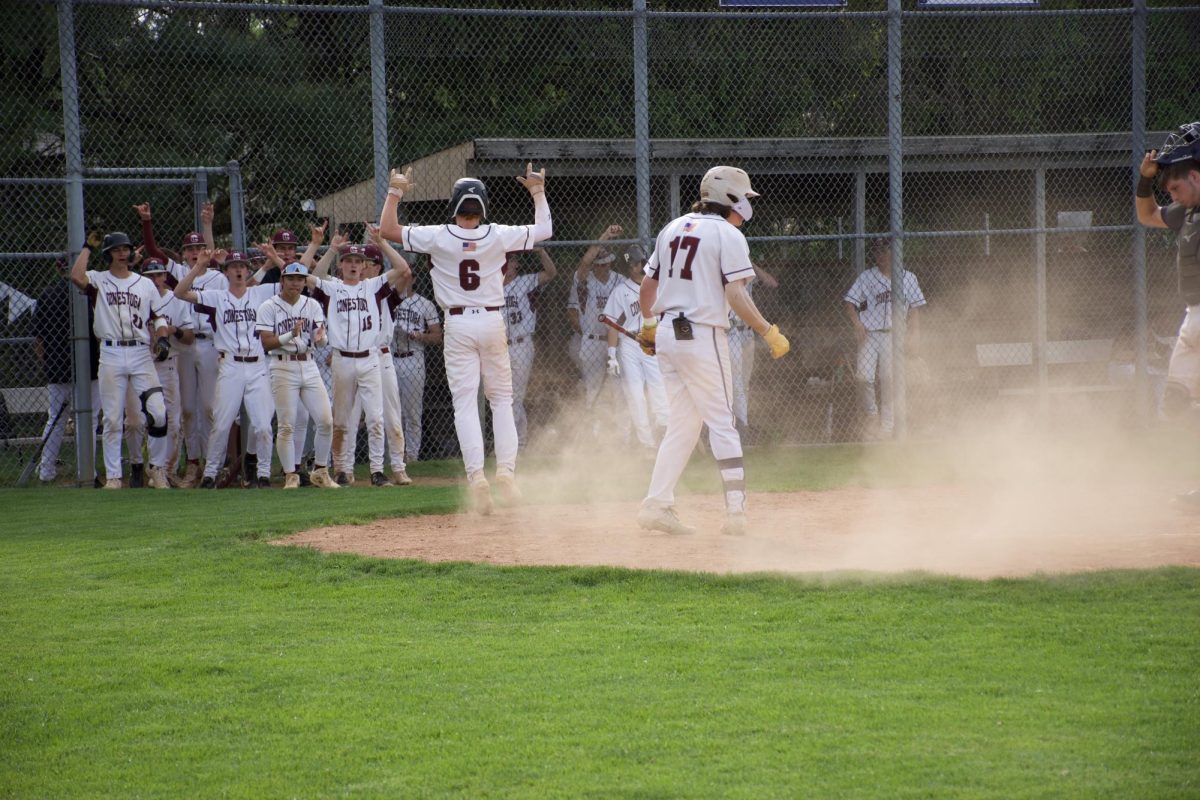

“I’m just glad that the judge heard us and it was evident to her that there is a gap in funding in the state of Pennsylvania in public schools,” said Dr. Eric Becoats, Superintendent of the William Penn School District in Delaware County. “I am hopeful that this will begin to change the trajectory for public schools going forward, especially those who have populations of students who have needs that we don’t necessarily control.”

Current system’s effects on less affluent school districts

The six school districts that joined as plaintiffs united over a common concern, but the problems each faces due to inadequate funding vary.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit William Penn School District, Becoats struggled to ensure that all students could attend classes virtually due to an inability to provide the resources needed to support virtual learning.

“The district sent one Chromebook home to every family when schools were shut down. So imagine having three children who have to share a Chromebook and be educated, and all of them are in school within the same span of time during the day, for the most part. That’s challenging,” Becoats said.

The COVID-19 pandemic additionally brought up new conversations surrounding mental health. For many students, access to mental health resources is limited to their educational environment. Becoats finds that the William Penn School District was — and still is — unable to provide this service to its students.

“We are not able to obtain some basic resources that you would expect to have in a school district. We do not have a social worker at every school. This is the first year that we’ve had three, and we have 11 schools. So the social workers are split by level: elementary, middle and high school,” Becoats said.

Similarly, the School District of Lancaster in central Lancaster County saw similar challenges following the COVID-19 pandemic. The district serves 11,300 students, according to Superintendent Matthew Przywara.

“A lot of our students just were not receiving the education they would have received in in-person instruction. We did a lot of hybrid or virtual instruction for a longer period of time than some other districts did, so we really need to make up (that) learning gap,” Przywara said. “Any money we would get is going to be toward filling those learning challenges or those learning gaps that we’ve been experiencing and really accelerating the learning for our students.”

While Przywara believes that the most important use of additional dollars within the School District of Lancaster is in closing the COVID-19 pandemic-created educational deficits, he also sees other problems that would benefit from additional state money. Established in 1836, the School District of Lancaster is Pennsylvania’s second oldest school district with buildings that are currently almost 100 years old and need renovations.

“We have buildings that date back to 1925-1935. So for us to renovate those buildings, that takes hundreds of millions of dollars. And we need that funding to help us do that and bring our schools up to the 21st century because some of our schools haven’t been renovated since 1965,” Przywara said.

The Wilkes-Barre Area School District is facing similar problems. It encompasses the city of Wilkes-Barre, as well as seven additional townships, and serves 7,900 students.

The district used to have three high schools, all of which were more than 100 years old, and consequently falling into disrepair, according to Times Leader, a media group that covers northeastern Pennsylvania.

“That (buildings’) facade was actually crumbling, so it was falling and it was big pieces, and it would have caused injury. So, there was actually fencing that went around this whole area. But unfortunately, because of the lack of funding, we just were unable to address just the physical need of our buildings,” said Dr. Brian Costello, Superintendent of the Wilkes-Barre Area School District.

Due to the safety concern and the inability to build any new schools, the administration of James M. Coughlin High School of the Wilkes-Barre Area School District’s moved the students into one of the elementary school buildings while the other half remained in the high school.

How the ruling could possibly affect TESD

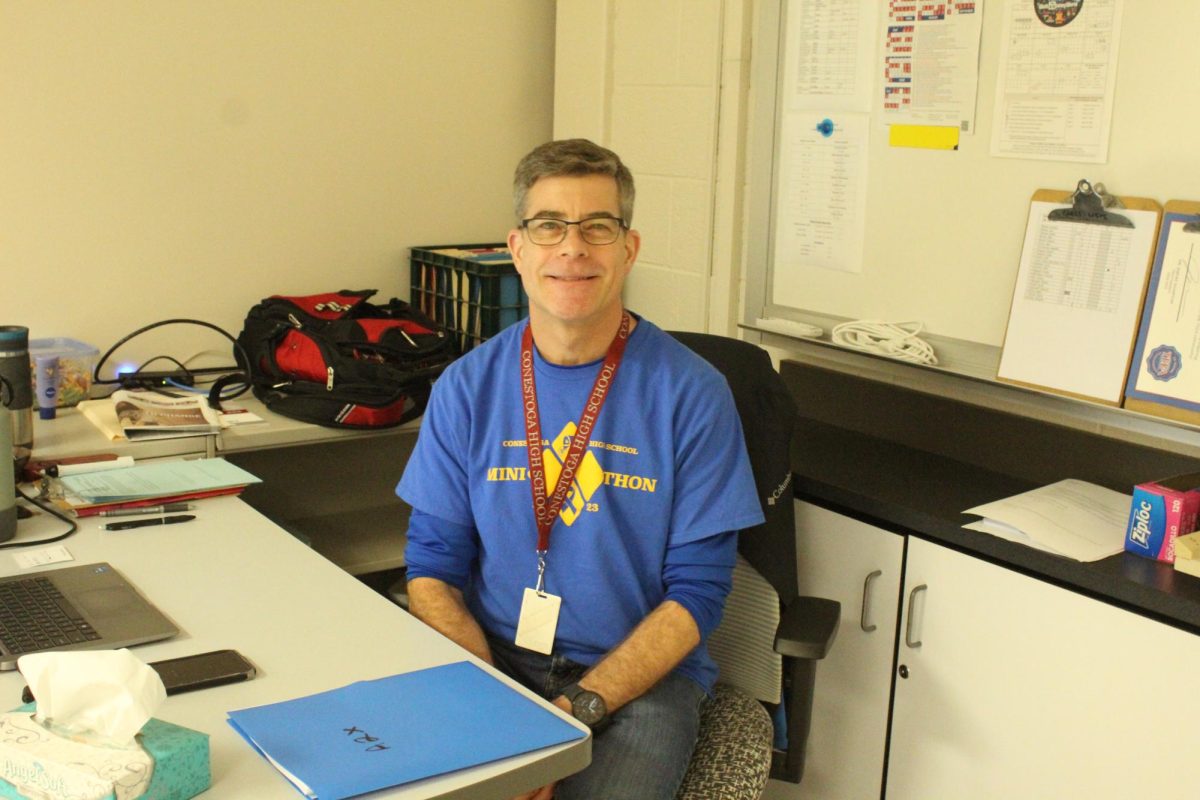

The Tredyffrin/Easttown School District serves just over 7,000 students. As the decision about state funding for Pennsylvania’s public school districts is not set in stone, TESD’s budget will not be affected as of right now, according to superintendent Dr. Richard Gusick.

“If (the Pennsylvania General Assembly) decides in the process to take money out of T/E — either by reducing our state formula or changing to an entirely different way of funding schools — where we’re left with net less money to spend on the educational program, then that’s something that I would strongly oppose,” Gusick said.

Each year, every Pennsylvania public school district fills out an estimated budget summary for the upcoming academic year that breaks down funds between local, state and federal sources.

Based on the estimated funds for this school year as of June 2022, in TESD, about 15%, or $25 million, comes from the state, while 84%, or $134 million, comes from local funding which is based on property taxes. Only 0.8%, or $1 million, comes from the federal government and other sources.

In comparison, the Wilkes-Barre Area School District’s summer estimates placed the value of local funds around 45%, or $66 million, of this academic year’s funding. The district relies on the state’s 37%, or $54 million, and the federal government’s 18%, or $26 million, to make up for the smaller proportion of local funding.

Gusick acknowledges this discrepancy and would prefer a solution that supports the districts that need more funding without taking away from that of TESD.

“If (the Pennsylvania General Assembly) just tried to bring the level of funding up in other districts to a certain level without taking anything away from us,” Gusick said, “I’m not really as concerned.”

Ben Shapiro can be reached at [email protected].

Remington Vaughan can be reached at [email protected].