By Shreya Vaidhyanathan, Opinion Editor

In December 1965, 13-year old Iowa student Mary Beth Tinker and her classmates wore black armbands to school in protest of the Vietnam War. School administrators quickly retaliated under the narrative that the students had disrupted the school day, passing a rule to ban armbands and suspending students who had participated in the demonstration.

The students’ parents challenged the suspensions on the grounds of the First Amendment and, upon losing at the federal level, appealed the decision and eventually made it to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in favor of the students, declaring that neither students nor teachers “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

Today, this conversation has shifted to focus largely on student journalists. The Tinker standard — the policy that schools may not censor student expression unless proven that they are disruptive to the school day or invading the rights of others — has since been adopted by schools across the country, becoming a baseline of the fight against censorship.

Now more than ever, scholastic and local journalism is important. Between local papers falling through the cracks during the COVID-19 pandemic and TV news organizations rising rapidly in popularity and revenue, as reported by the Pew Research Center, the lack of local newspapers is glaring.

Nonprofit media advocacy organization Poynter Institute writes that many school papers had to switch to online or otherwise adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, a professor Penelope Abernathy at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s School of Media and Journalism reported that “the rise of the ghost newspaper” is prominent. In other words, local newspapers becoming less consistent is a loss for communities. Therefore, school papers are stepping into the role of covering local news and becoming papers of record for their community.

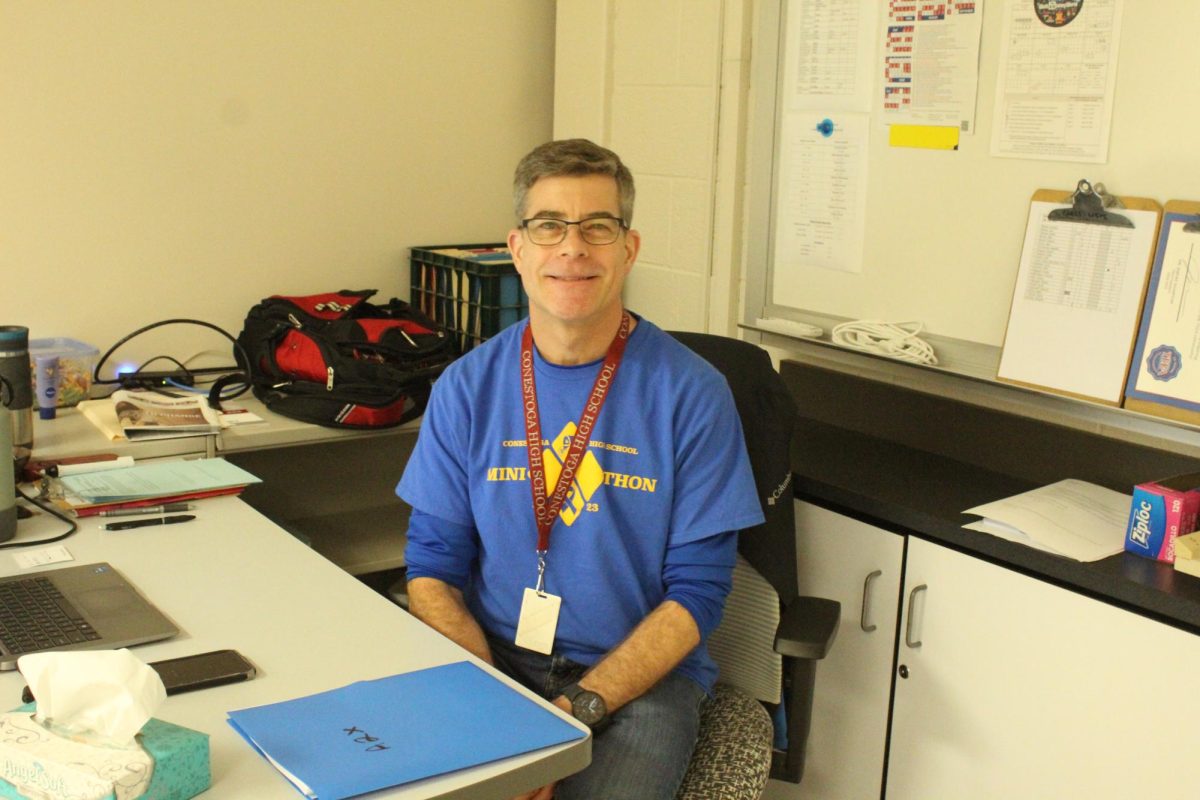

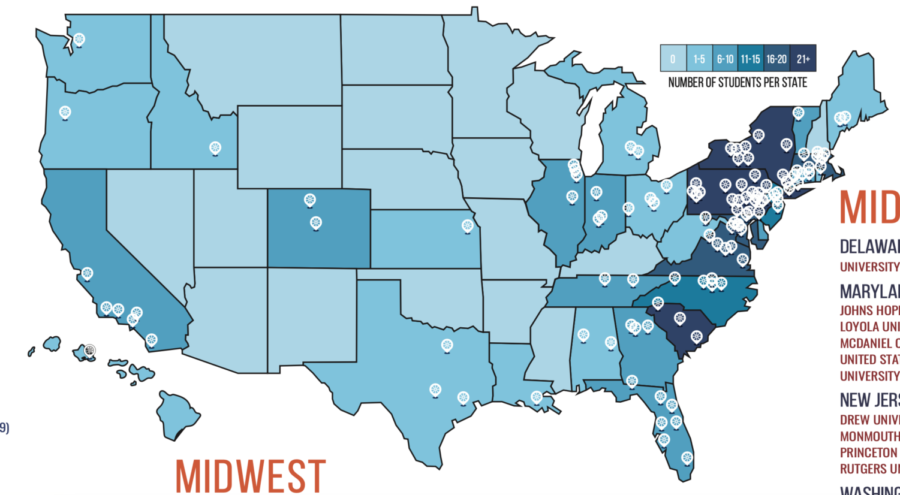

This resurgence of student media is exactly why Pennsylvania needs the Student Journalism Protection Act. The bill ensures that student journalists have the authority to determine their own content and that their media cannot be censored, save for certain rare circumstances. Additionally, the act provides protection for educators who refuse to censor students from professional repercussions. Similar legislation has already been passed in 15 states, and their Pennsylvania counterpart is currently awaiting introduction in the Pennsylvania House and Senate. At the time of publication, Representative Melissa Shusterman and Senator Carolyn Comitta have verbally committed to sponsoring this bill.

Pushback against this bill comes from the ruling in Supreme Court case Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier that public schools should be able to disallow student speech if it conflicts with the school’s educational mission, supporting the idea that the First Amendment offers less protection to student publications in public schools than to independently-established student papers or forums for student expression.

This standard, however, contradicts the idea established in Tinker v. Des Moines and lessens the impact and capabilities of student journalists. As Justice Hugo wrote in his concurring opinion on New York Times Co. v. United States, “the purpose of the press is to serve the governed, not the governors.” The same logic can and should be applied at a scholastic level; the purpose of school newspapers is to serve the students, not the administration.

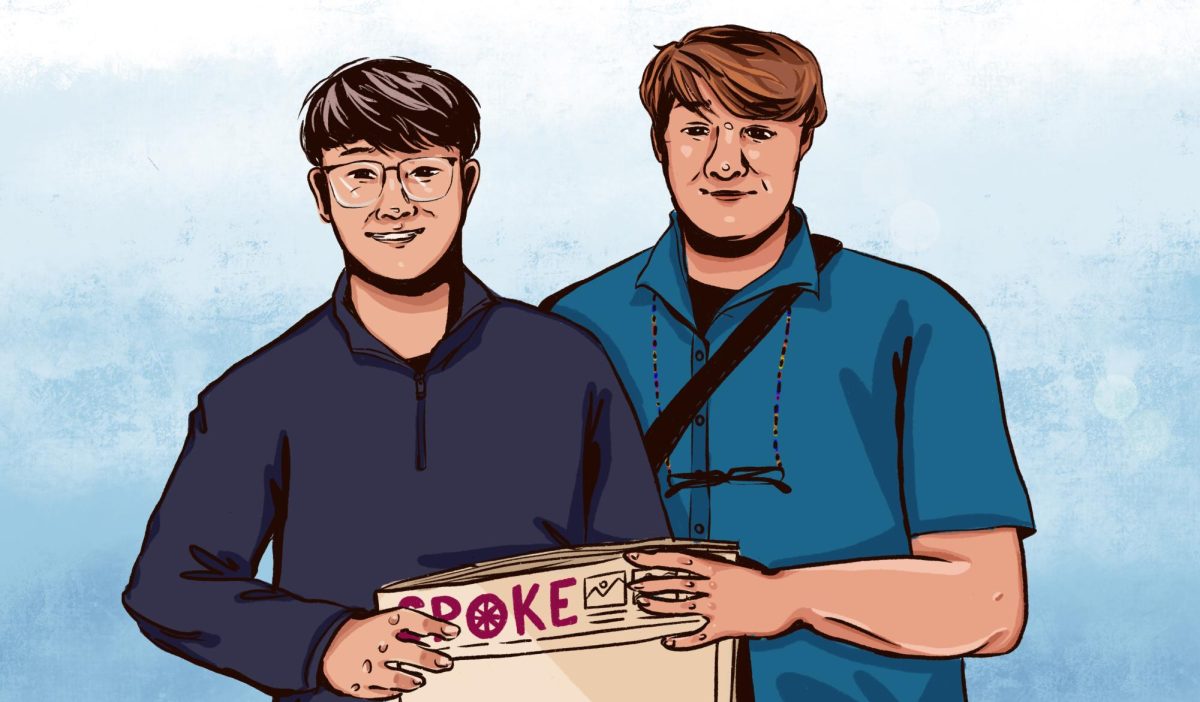

Scholastic journalism can be a positive experience for anyone, not solely for those who plan to pursue it; our own Spoke alumni credit their time on The Spoke for strengths like interviewing skills and positive time management habits. Peer-reviewed journal Higher Education Review writes that school newspapers can “improve the quality of education in your institution,” improving communication and boosting the educational process.

Cementing students’ rights to self-expression with this legislation is vital to the preservation of scholastic journalism. If any of this work speaks to you, please reach out to the [email protected] and join the Pennsylvania New Voices task force, the driving force behind grassroots lobbying to get this legislation passed. We cannot cement these rights without the strength and support of the people.

Shreya Vaidhyanathan can be reached at [email protected].