By Nishka Avunoori and Abbie Preston, Staff Reporters

National inclusion experts recently hosted the PA Inclusion Collective, a series advocating for inclusive educational opportunities in schools, over Zoom from Feb. 3-24.

Inclusive education provides students with disabilities with improved learning and social experiences, teaching them how they can be equal counterparts in society when they get older. Throughout the event’s four sessions, presenters touched on why inclusive education matters, how to incorporate it in schools and in online learning and how parents and educators can support students with behavioral challenges.

“I think (the attendance) really says a lot about the appetite and hunger in our community,” said Maggie Gaines, a mother of a disabled child and co-leader of BUILD T/E, one of the sponsors of the event. “People really want to know more about what it means to be inclusive, how we can make sure that all students are included, and that includes students with disabilities.”

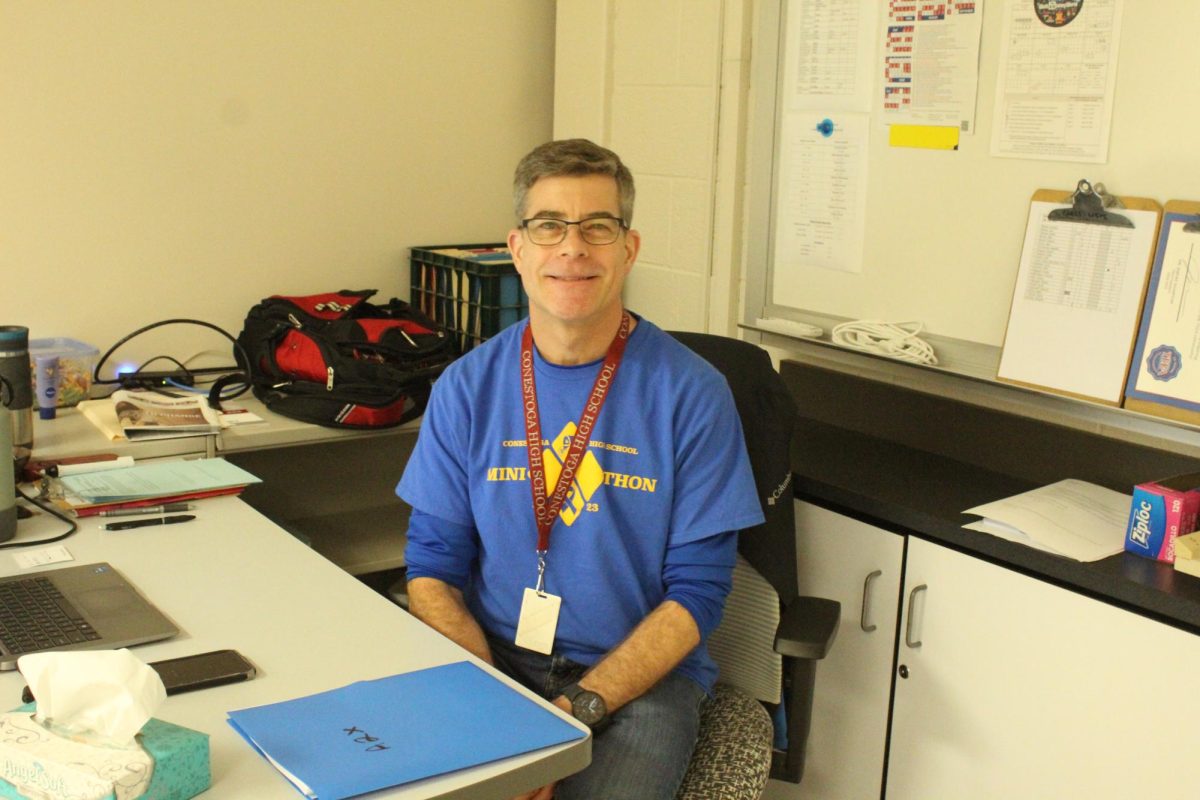

Dr. Causton, CEO of Inclusive Schooling, and Dr. Pretti-Frontczack, CEO of B2K Solutions, led the discussions in the PA Inclusion Collective, focusing on what school systems across the country lack in terms of inclusion. Throughout the event, Causton and Pretti-Frontczack stressed the importance of educating students with and without disabilities together.

“There is this negative connotation that suggests that you’re so different that you have to be somewhere else when in reality, we are all human beings,” Causton said. “Every one of us has skills and deficits.”

Causton also states how the nation as a whole needs to think about equity as a bigger construct. Those that are traditionally marginalized should be given the same access to education.

“The goal of special education and inclusive education is to level the playing field so that every human has the same advantages that everyone else has,” Causton said.

Otto Lana, a sophomore at Fusion Academy in San Diego, California, made a teaching appearance in the series’ last session. Lana was diagnosed with autism and apraxia when he was 2 years old. After spending a decade in silence, Lana met a speech therapist who taught him to use a keyboard to communicate.

“I have always been just me. I think (my autism diagnosis) changed the way the world experienced me. I think it allowed the world to stuff me in a box and store me on a shelf on the Island of Misfit Toys,” Lana said.

Gaines notes the strides society had made since forty years ago when children with disabilities were sent to an entirely different school. Though improvements have been made, Gaines still believes that there is a stigma around disabilities that needs to be changed.

“It’s 2021, and I still feel like I have to educate a community; it’s a little tiring. It seems kind of crazy that we have to remind people that this is what it’s supposed to be, but at the same time, this is a hearts and minds exercise,” Gaines said. “People have to believe it in their hearts and understand that people with disabilities are not people to be sad for; they are human beings.”

Lana suggests that schools be patient and open to new ideas. He has found that younger students are more accepting of students with differences but develop a fear of being different as they grow older. For him, inclusive education is a personal preference; it means access to support and a meaningful curriculum to meet his goals.

“I learned there are even more allies than opposers fighting and cheering for equality and individuals with differences,” Lana said. “You cannot have an equal society if individuals are separated: separate is not equal.”

Nishka Avunoori can be reached at [email protected].

Abbie Preston can be reached at [email protected].