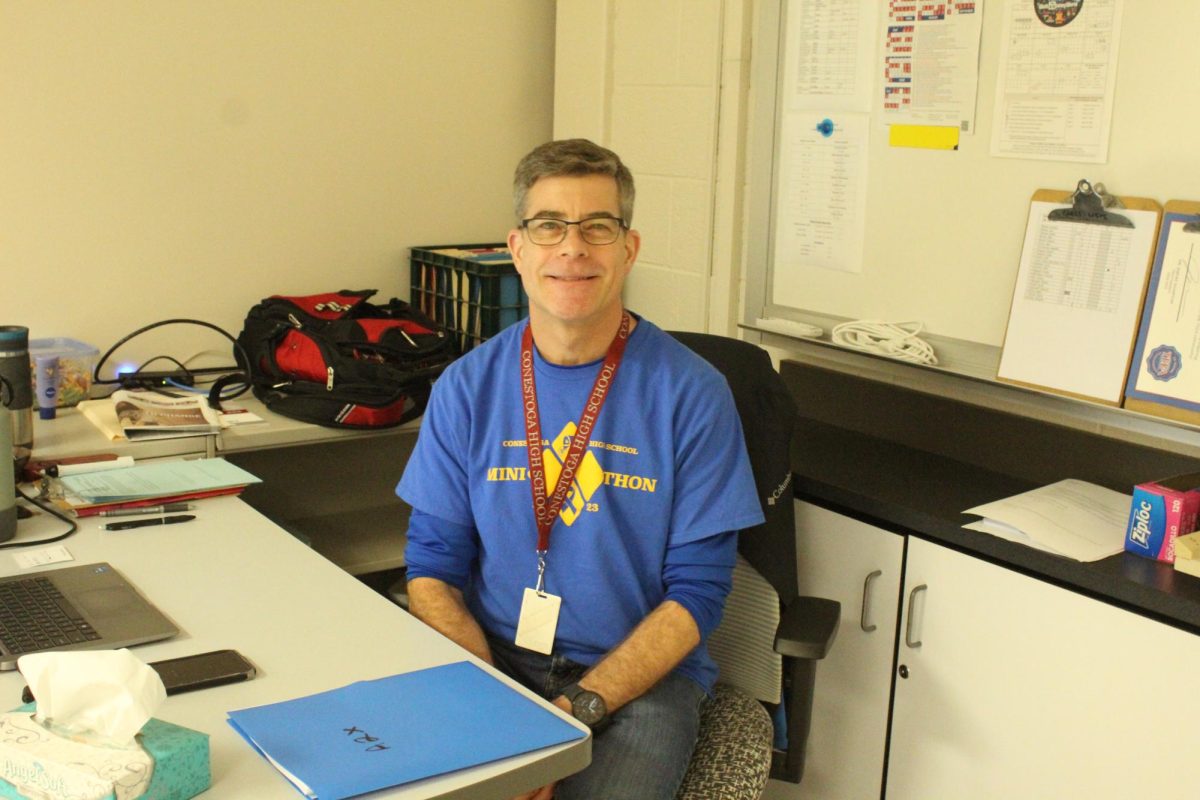

By Matthew Fan, Staff Reporter

Grades are percentages—100, 90, 80—so it would make sense that they represent the percent of the class material that a student has mastered, but that’s not the case, especially at Conestoga High School, where grades are often inflated. What’s the point of having a grade if it doesn’t properly reflect how much of the material you have learned? It’s not that I’m disappointed that I have a better chance of ending with an A in difficult AP classes, but if you want to evaluate a student’s understanding of a subject, don’t look at grades.

There’s one fundamental flaw in the grading system that dominates most Conestoga classes— total points. In the total points method, each assignment has equal value, with the grade calculated by this equation: [(total points earned)/(total points possible)]*100%. If a class uses total points, you can have an average score of a B in tests yet still have an A in the class by earning full points on homework and projects, which require more effort than mastery. As a result, a grade based on total points does not properly represent a student’s comprehension.

This limited comprehension presents a problem because students are not adequately prepared for college. In fact, the National Center for Education Statistics, a subset of the U.S. Department of Education, reported that 40 percent of students starting at public four-year institutions took at least one remedial course during their enrollment between 2003 and 2009. Remedial courses are designed to strengthen academic skills, so remediation is concentrated among students who lack academic preparation, which can stem from a high level of leniency—in other words, grading based on effort, not mastery of a subject. While the rigor of Conestoga’s classes does help prepare students for college courses, grading students on effort can still leave students unprepared because college grades are mostly based on tests and papers.

Some may argue that switching to a weighted grading system—which assigns each category, such as tests and homework, a percentage of the total grade— for all classes resolves this grade inflation problem. Though it will help, it is not enough. Most classes that use this system give extra credit to students on tests or quizzes. Also, there are many incidences of cheating that crack the mirror of grades even more. For example, if you were to walk into one of my classes during an open-note quiz (which allows students to only use notes written by themselves), you would see some students searching up answers on the Internet or sifting through a PDF of the textbook. In this case, quiz grades, which are weighted in this class, are not representative of mastery.

But why, then, are open-note quizzes still given out when cheating is extremely likely? Likewise, why do projects, which do not necessarily require mastery and can be seen as “easy points, ” nonetheless have high point values? Quizzes are usually used to test whether a student understands one part of a larger unit, serving as checkpoints before the test to identify what a student needs to study, so they are influential in helping students comprehend the material. Similarly, projects serve to reinforce concepts, which in turn helps prepare students for exams. To address this conundrum of costs and benefits, it would be easiest to make quizzes closed-note or strictly enforce all quizzes to be taken on Lockdown Browser (a program that keeps students from leaving the window with the assessment), with the option of allowing students to use hand-written notes. Projects should not be worth that many points because it is more important that they help the student understand rather than simply give a grade boost.

There is no easy way to make grades reflect mastery. Yes, we could completely switch to the weighted grading system, and teachers could stop giving extra credit, but the school would never implement this for every class. The average grades in all classes would plummet, and that would reflect poorly on the school. I believe the only way for people to see whether a student has mastered a subject is to look at a standalone examination, such as an AP Exam, but adapt it for all course levels. Alternatively, midterms and finals could be used, but currently, they are not “standalone,” as they do not appear on the report card as a separate grades. Rather, they are factored into the overall grade for the class. Therefore, until there’s a standalone examination for every class, grades should not used to see if a student has mastery of a subject